THE CITY OF INDRO

“What I have become I owe to Milan but what I am, what my character is, I owe it to Fucecchio”.

With these words, repeated several times, Indro Montanelli (1909-2001) expresses the deep bond with his hometown, a root that was the basis of his personality, of the frankness with which he conducted his battles, of his own writing, dry and incisive. Once he confessed: “Perhaps in my life I have always looked for Fucecchio”, a place that had remained in his heart, despite his success and his countless trips to all continents. Paraphrasing the words of the great journalist, this itinerary invites you to look for Montanelli in his beloved Fucecchio.

For more information on Montanelli’s work and the activities promoted by the Montanelli Bassi Foundation, visit the website www.fondazionemontanelli.it.

Il sogno di Montanelli

MY NAME IS INDRO

My name is Indro.

“The reasons why I was given this name at the baptismal font are very complex and have a political and social content. I want to tell you about them because from them you can get many insights about my origin and the environment in which I was born and raised.

You must know that Fucecchio, my homeland, is a town in the Valdarno, located halfway between Pisa and Florence. It is a fairly ancient town, which developed around the feudal core of a Florentine castle, as are many towns in that district. […] Over time, the town began to descend towards the plain, the Arno and its streets. Here it settled down and began to swell mainly as an agricultural market. Since it is a good rule of every Tuscan village to always divide into two factions, Fucecchio was divided into “insuesi” and “ungiuesi”. The insuesi were those who stood up, that is, in the old part, around the castle and the Collegiate Church; those who were on the way down, that is, along the provincial roads leading to Florence, Pisa and Lucca, were unjust.

[…] The marriage between my mother, insuese, and my father, ingiuese, was one of the big business of the pre-war Fucecchio. My mother belonged to the Dondoli family which was, as I have said, one of the most conspicuous, perhaps the most conspicuous, of the insane families. I don’t know exactly where this house came from because my genealogical knowledge doesn’t go back further than my grandfather. But I don’t think it was very old in the place. Its strength came more from money than from tradition. The palace, which was the most sumptuous in all of Fucecchio, had been bought by my grandfather Alessandro, who kept a counter for wholesale cotton trading there. […] Rosamunda – who was a beautiful woman, with a cold and merciless beauty like her eyes – had seven children by Alessandro, four boys and three girls: my mother Magdalene was the fifth. She gave birth to them without a moan and raised them without a caress, determined to sacrifice all the females for all the males.

Of the four male offspring, two studied and became a lawyer and the other a doctor; and two, on the other hand, to Rosmunda’s great despair, did not feel like it. The lawyer followed the schools in Florence, then in Switzerland and finally in Pisa. When he was in Florence, he was a schoolmate of my father, of whom it is time to talk to you.

My father was unjust and from an obscure family, although there are, in Fucecchio, some quite famous Montanellis because of a revolutionary of ’48 to whom the Fucecchiesi have dedicated a monument. But the Montanellis my father belonged to were from another branch, the poor branch obviously, and my grandfather Raffaello had an oven. […] His wife Edvige, known as Eduige, was at the bakery, who also ran a restaurant and who, active and stingy, ran a family of four children: one girl and three boys. Of the boys, my father Sestilio was the most promising, he studied well and with excellent results; therefore the hopes and resources of the family concentrated on him and decided to make him a professor of literature. […] At school he was the companion of Alberto Dòddoli who, very intelligent and lazy, let Sestilio do his homework. The latter, returning from holidays in the village, the friendship with Alberto allowed him to ascend to Palazzo Dòddoli and meet my mother there. You can imagine the rest. But do not imagine, instead, the war that Rosmunda waged against Sestilio who, by dint of repetition, managed to get Curtatone, the seventh of the Dondoli sons, to take his high school diploma. A little bit of this, a little bit of the intercession of the mayor and the archpriest, finally allowed my father to get pregnant with my mother. […]

The latter, who was then teaching the techniques of the country, took his wife downstairs to a house with a garden, and, having obtained the pardon, fully embraced his subversive ideas. Shortly after, my mother became pregnant. Immediately Rosmunda descended from the hill to take back her daughter so that the heir could be born upwards. In fact, I was born on April 22, 1909. But shortly after, Rosmunda having become ill, my father came to take back his wife and offspring and, to avenge himself, he obstinately began to search for me a name that was neither in the family. , nor in the calendar.

I find it”.

From “People whatever”, Bompiani 1942, in Anthology of Fucecchiesi writers, Edizioni dell’Erba (1990)

The rooms, the villa, the resting place

“The only advice I feel I can give – and which I regularly give – to young people is this: fight for what you believe in. You will lose, as I did, all the battles. But only one can win. The one who hires himself every morning, in front of the mirror”.

The rooms of Indro

In Fucecchio, an itinerary dedicated to this extraordinary figure of the twentieth century can only start from the Montanelli Bassi Foundation (www.fondazionemontanelli.it), which he himself established in 1987. Here, in the rooms full of history and suggestions of the Palazzo della Volta he still feels the unmistakable presence of Indro.

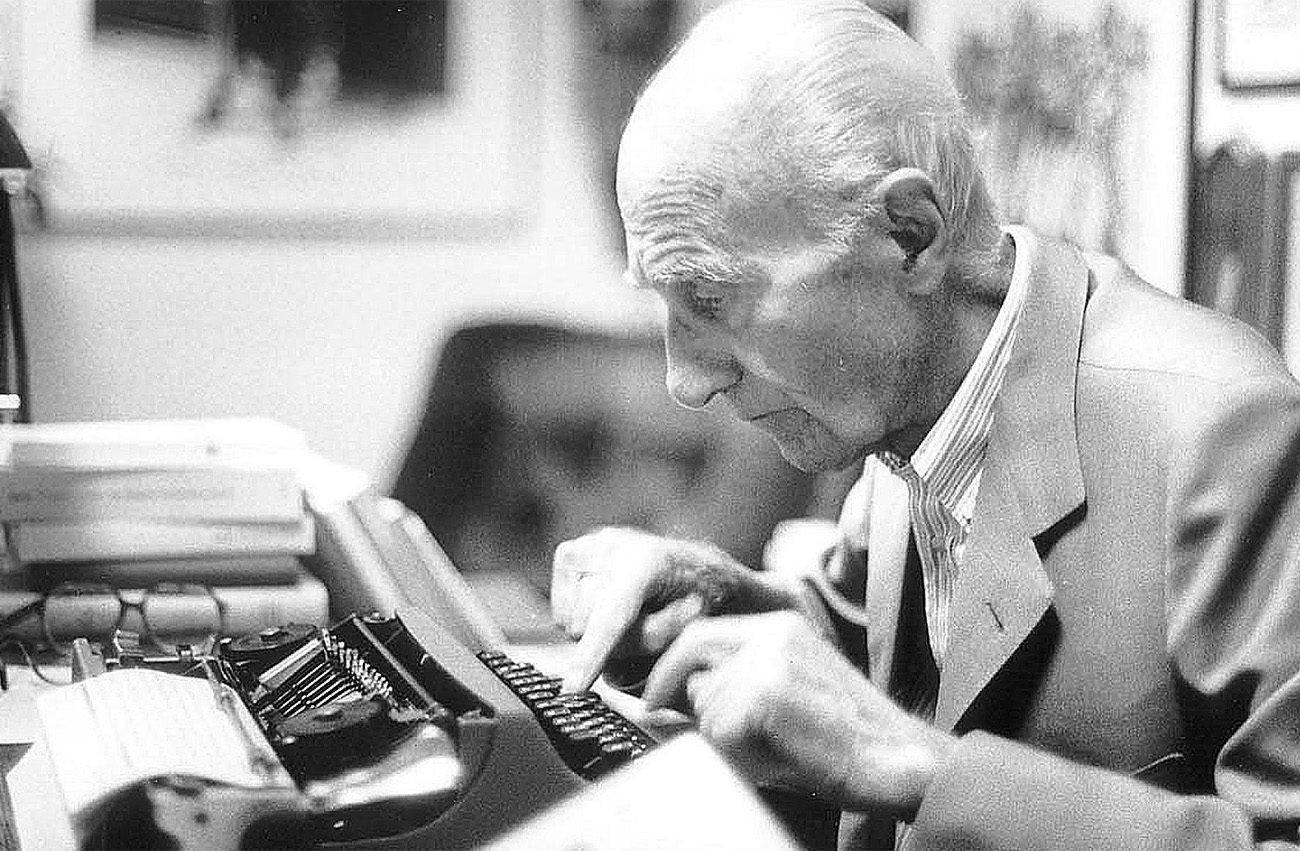

Since 2001, by testamentary will, the Foundation has housed the studios in Milan and Rome, transferred here in full, with all the books, papers, personal objects and furnishings, which better tell of any biography, the personality and passions of Montanelli.

Entering the Milanese studio, one is led to approach the solid wooden desk, built by the “grandfather” Emilio Bassi at the beginning of the twentieth century, where the famous Lettera 22 typewriter “rests”, after many years of work under the tireless fingers by Indro.

The agenda with the latest appointments, the favorite armchair, the books autographed by other famous writers, the photographs in the Roman studio and the library, where all his works are kept, reveal a hidden and more intimate side of the journalist than in these rooms appear less distant. Montanelli’s bond with his Fucecchio is also testified by the presence of a collection of works by fellow citizen Arturo Checchi, which he wanted to donate to his Foundation.

Villa Bassi, or the cherry garden

In the nearby town of Vedute, there is another place that was very dear to Indro: it is Villa Bassi, where as a boy he spent a lot of time as a guest of the family of the Mayor Emilio Bassi, whose children were tutored by Montanelli’s father. In his writings, the journalist speaks of the villa as the “cherry garden” and confesses his “dream of views”, in which he imagined returning to this place of his youth and meeting another himself, who accused him of having betrayed its roots. The villa is privately owned but is still visible from the street.

The farewell of an “including genius”

Montanelli’s ashes rest in an urn inside the family tomb in the municipal cemetery of Fucecchio. Perhaps not everyone knows it, but Indro, since the 1950s, had the habit of noting here and there, where he happened, hypothetical epitaphs for the graves of famous people who, in the course of his long and adventurous life, had the opportunity to meet. And he certainly did not spare himself for which he wrote with great self-irony:

Genius included

he explained to the others

that is

that he himself

he did not understand.

The entire collection of sharp epitaphs is instead collected in the amusing essay Ricordi sott’odio. Sharp portraits for excellent corpses (Rizzoli, 2011).

Freedom in a tape

On Saturday 22 April 2017, Marco Puccinelli’s sculpture entitled “Freedom in a tape – Letter 22”, dedicated to the figure of Indro Montanelli, was inaugurated in Fucecchio. Made of stainless steel, an eternal material like the thought of the journalist from Fucecchio, the work was discovered on the occasion of the renovation of Piazza della Ferruzza. This is how the artist talks about it:

“The idea of a sculpture dedicated to Montanelli was born in 2008, immediately after the realization of the work for Enzo Biagi. I was born in Fucecchio, was from Fucecchio, it seemed a natural consequence to dedicate a sculpture to our most illustrious fellow citizen.

For my part, however, I want to emphasize that this is not just a parish aspect, there is great esteem for the writer and journalist Montanelli, in my opinion the greatest. As for the fact that Montanelli, during his life, recalled several times that he did not like a monument, I can say this: my work does not represent his image but his thoughts, the facts he told and his ideas. sometimes uncomfortable.

All this imprisoned in the tape of the typewriter as if it were for me the palette with colors and brushes. My work is a synthesis of his thinking. I have absolutely not looked for a representation of the image”.

Previously Puccinelli had already made a sculpture, also in steel, for another great journalist: Enzo Biagi, honorary citizen of Fucecchio since 2002. The work, entitled “Peace in a pen”, was inaugurated in 2008.